Popular blog

File 770 has a post by JJ on

Where To Find The 2020 Hugo Award Finalists For Free Online, a useful resource for anyone wanting to start reading before the Hugo Voter Packet becomes available. But what of the 1945 Retro Hugo Awards finalists? There is unlikely to be a Voter Packet for these, so how are Hugo Awards voters to go about making an informed choice here? Fortunately, many of the works that will be on the ballot are available online, either on the

Internet Archive or elsewhere. Below I have compiled links to as many of these as I could find, and provided information about whether items are in print or otherwise. If any of the links do not work, please let me know in the comments.

Best Novel

- The Golden Fleece, by Robert Graves (Cassell & Company). Also known as Hercules, My Shipmate, this retelling of the Jason and the Argonauts story is in print and available from book stores and online retailers.

- Land of Terror, by Edgar Rice Burroughs (Edgar Rice Burroughs, Inc.). Ebook versions of this can be purchased online. It is also out of copyright in Australia, so can be read on that country's Project Gutenberg.

- "Shadow Over Mars", by Leigh Brackett (Startling Stories, Fall 1944). Subsequently published as the standalone novel The Nemesis from Terra, which appears to be out of print, but the magazine it first appeared in can be read or downloaded on the Internet Archive.

- Sirius: A Fantasy of Love and Discord, by Olaf Stapledon (Secker & Warberg). In print and readily obtainable.

- The Wind on the Moon, by Eric Linklater (Macmillan and Co.). In print and readily obtainable.

- "The Winged Man", by A. E. van Vogt and E. Mayne Hull (Astounding Science Fiction, May-June 1944). Originally serialised in Astounding, this was subsequently published as a complete novel but appears to now be out of print. It can be read in the May and June 1944 issues of Astounding Science Fiction on the Internet Archive.

Best Novella

- "The Changeling", by A E van Vogt (Astounding Science Fiction, April 1944). This has also been published as a chapbook but is now long out of print.

- "A God Named Kroo", by Henry Kuttner (Thrilling Wonder Stories, Winter 1944).

- "Intruders from the Stars", by Ross Rocklynne (Amazing Stories, January 1944). This has also been published in one volume with Malcolm Smith's "Flight of the Starling", in which format it may be available from online booksellers.

- "The Jewel of Bas", by Leigh Brackett (Planet Stories, Spring 1944). This has also appeared in collections of Brackett's work.

- "Killdozer!", by Theodore Sturgeon (Astounding Science Fiction, November 1944). This can also be found in various anthologies of Golden Age science fiction; see its ISFDB entry for more details.

- "Trog", by Murray Leinster (Astounding Science Fiction, June 1944).

Best Novelette

- "Arena", by Fredric Brown (Astounding Science Fiction, June 1944). This can be read in print in various anthologies, of which The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One, 1929-1964 appears to be readily available. See also its ISFDB entry.

- "City", by Clifford D. Simak (Astounding Science Fiction, May 1944). This also appears as a chapter in the readily available novel of the same name. If you want to read all the nominated pieces from City in publication order, read this one first.

- "No Woman Born", by C. L. Moore (Astounding Science Fiction, December 1944). This can also be found in anthologies of Golden Age science fiction. See its ISFDB entry for more details.

- "The Big and the Little", by Isaac Asimov (Astounding Science Fiction, August 1944). As "The Merchant Princes", this appears in the novel Foundation. If you want to read the two stories from Foundation in publication order, read this second.

- "The Children's Hour", by Lawrence O'Donnell (C. L. Moore and Henry Kuttner) (Astounding Science Fiction, March 1944).

- "When the Bough Breaks", by Lewis Padgett (C. L. Moore and Henry Kuttner) (Astounding Science Fiction, November 1944).

Best Short Story

- "And the Gods Laughed", by Fredric Brown (Planet Stories, Spring 1944). This also appears in anthologies of Brown's work.

- "Desertion", by Clifford D. Simak (Astounding Science Fiction, November 1944). This also appears as a chapter in the novel City. If you want to read the nominated stories from City in publication order, read this third.

- "Far Centaurus", by A. E. van Vogt (Astounding Science Fiction, January 1944). This can also be found in general anthologies and ones of van Vogt's work. For further details see its ISFDB entry.

- "Huddling Place", by Clifford D. Simak (Astounding Science Fiction, July 1944). This also appears as another chapter in the novel City. If you want to read the nominated stories from City in publication order, read this second.

- "I, Rocket", by Ray Bradbury (Amazing Stories, May 1944). A replica edition of this issue of Amazing Stories can be purchased online.

- "The Wedge", by Isaac Asimov (Astounding Science Fiction, October 1944). This also appears as "The Traders" in the novel Foundation. If you want to read the two stories from Foundation in publication order, read this first.

Best Series

Captain Future, by Edmond Hamilton

Written by Edmond Hamilton (sometimes using the pseudonym Brett Sterling), the

Captain Future stories appeared in the magazine of the same name.

Wikipedia has an overview of the series, while the

ISFDB has a listing of

Captain Future stories. A selection of these are available on the Internet Archive:

The Cthulhu Mythos, by H. P. Lovecraft, August Derleth, and others

The deity Cthulhu first made its monstrous appearance in H. P. Lovecraft's 1928 short story "The Call of Cthulhu". Subsequently much of Lovecraft's and his associates' work has been grouped together under the

Cthulhu Mythos label. Like many of the horrors Lovecraft deals with, the

Cthulhu Mythos is somewhat amorphous and it can be difficult to fix its exact boundaries. Not all of Lovecraft's own stories are unambiguously part of the Mythos, while one can argue as to whether some of the works by his admirers are truly part of the Mythos or deviations from the true path.

Wikipedia attempts a rough overview of the Mythos, while the

ISFDB attempts a bibliography. Note that the Mythos remains a living tradition, with stories continuing to be published, but only those that had appeared by the end of 1944 should be considered by Retro Hugo Awards voters.

There are numerous in-print anthologies of Lovecraft's own fiction. The Internet Archive also has scans of the magazines in which some of these originally appeared, including

"The Call of Cthulhu" (

Weird Tales, February 1928),

"The Dunwich Horror" (

Weird Tales, April 1929),

"The Whisperer in Darkness" (

Weird Tales, August 1931),

"The Music of Erich Zann" (

Weird Tales, November 1934),

"The Haunter of the Dark" (

Weird Tales, December 1936),

"The Shadow out of Time" (

Astounding Stories, June 1936),

"The Thing on the Doorstep" (

Weird Tales, January 1937), "The Case of Charles Dexter Ward" (

Weird Tales, May 1941 &

Weird Tales July 1941),

"The Colour Out of Space" (

Famous Fantastic Mysteries, October 1941), and

"The Shadow over Innsmouth" (

Weird Tales, January 1942).

The

Cthulhu Mythos was developed and expanded by writers associated with and inspired by Lovecraft. August Derleth co-founded Arkham House to keep Lovecraft's fiction in print; he also wrote Lovecraftian fiction of his own, including

"The Thing That Walked on the Wind" (

Strange Tales of Mystery and Terror, January 1933),

"Beyond the Threshold" (

Weird Tales, September 1941),

"The Dweller in Darkness" (

Weird Tales, November 1944), and

"The Trail of Cthulhu" (

Weird Tales, March 1944). Frank Belknap Long gave us

"The Space-Eaters" (

Weird Tales, July 1928) and

"The Hounds of Tindalos" (

Weird Tales, March 1929). Robert Bloch wrote

"The Shambler from the Stars" (

Weird Tales, September 1935). Robert E. Howard gave us

"The Black Stone" (

Weird Tales, November 1931),

"The Children of the Night" (

Weird Tales, April-May 1931),

"The Thing on the Roof" (

Weird Tales, February 1932), and

"Dig Me No Grave" (

Weird Tales, February 1937).

Doc Savage, by Kenneth Robeson/Lester Dent

Published under the pseudonym Kenneth Robeson, the

Doc Savage stories were mostly but not entirely written by Lester Dent.

Doc Savage novels appeared at a phenomenal rate, starting in 1933, with 142 having been published by the end of 1944. The

ISFDB has a terrifyingly vast entry on the series, while

Wikipedia has summaries of the novels.

The Shadow's Sanctum is currently publishing reprints of the

Doc Savage novels.

Jules de Grandin, by Seabury Quinn

Seabury Quinn wrote a lot of stories featuring his occult detective Jules de Grandin.

Wikipedia has a short overview of the series, while the

ISFDB entry could be cross-referenced with the

Internet Archive to source scans of the issues of

Weird Tales in which the stories first appeared. Here is a somewhat random selection of stories in the series, including the first one published and the only one from 1944:

"The Horror on the Links" (

Weird Tales, October 1925),

"The House of Horror" (

Weird Tales, July 1926),

"Restless Souls" (

Weird Tales, October 1928),

"The Corpse-Master" (

Weird Tales, July 1929),

"The Wolf of St. Bonnot" (

Weird Tales, December 1930),

"The Curse of the House of Phipps" (

Weird Tales, January 1930),

"The Mansion of Unholy Magic" (

Weird Tales, October 1933),

"Suicide Chapel" (

Weird Tales, June 1938), and

"Death's Bookkeeper" (

Weird Tales, July 1944).

Pellucidar, by Edgar Rice Burroughs

The

Pellucidar stories are set inside the Earth, which in the first instalment is revealed to be hollow.

At the Earth's Core, the first

Pellucidar novel, appeared in 1914, while

Land of Terror, the 6th,was published in 1944.

Wikipedia's entry for the series links off to plot-summarising entries for the individual books. These are beginning to slip out of copyright, though the later ones are still not in the public domain everywhere. Readers can access the

Pellucidar at these links:

If a whole novel of hollow earth adventure is too much, there were also three pieces of short

Pellucidar fiction published in 1942:

"Return to Pellucidar" (

Amazing Stories, February 1942),

"Men of the Bronze Age" (

Amazing Stories, March 1942), and

"Tiger Girl" (

Amazing Stories, April 1942).

The Shadow, by Maxwell Grant (Walter B. Gibson)

Tales of this proto-superhero appeared from 1931 onwards under the pseudonym Maxwell Grant but were mostly written by Walter B. Gibson. By the end of 1944 a vast number of

Shadow novels had appeared (286 if

Wikipedia is to be believed).

The Shadow's Sanctum is currently publishing reprints of books in

The Shadow series.

Best Related Work

- Fancyclopedia, by Jack Speer (Forrest J. Ackerman). The FANAC Fan History Project has scans of this encyclopaedia of 1944 fandom, as well as a hypertext version.

- '42 To '44: A Contemporary Memoir Upon Human Behaviour During the Crisis of the World Revolution, by H. G. Wells (Secker & Warburg). This does not seem to be in print but readers may be able to source copies from libraries or second hand book dealers.

- Mr. Tompkins Explores the Atom, by George Gamow (Cambridge University Press). No longer in print as a standalone book, this is available as part of Mr Tompkins in Paperback, which can be obtained from Cambridge University Press or online resellers. An edition combining the book with Mr. Tompkins Explores the Atom with Mr. Tompkins in Wonderland, another book by George Gamow, can be accessed on the Internet Archive.

- Rockets: The Future of Travel Beyond the Stratosphere, by Willy Ley (Viking Press). This appears to be out of print, but readers may be able to source copies from libraries or second hand book dealers. It can also be borrowed from the Internet Archive.

- "The Science-Fiction Field", by Leigh Brackett (Writer's Digest, July 1944). This was recently reprinted in Windy City Pulp Stories no. 13, which is readily available from online sellers.

- "The Works of H. P. Lovecraft: Suggestions for a Critical Appraisal", by Fritz Leiber (The Acolyte, Fall 1944). This can be accessed on FANAC.

Best Graphic Story or Comic

- Buck Rogers: "Hollow Planetoid", by Dick Calkins (National Newspaper Service). Originally appearing as a daily newspaper strip, this story appears not to be in print. Art Lortie has however made it available to Retro Hugo voters here.

- Donald Duck: "The Mad Chemist", by Carl Barks (Dell Comics). Originally appearing in Walt Disney's Comics and Stories #44, this story has been reprinted but not obviously recently (see entry in Grand Comics Database). It can be read on YouTube or as uploaded by Art Lortie.

- Flash Gordon: "Battle for Tropica", by Don Moore & Alex Raymond (King Features Syndicate). Originally a syndicated newspaper strip, this was reprinted by Kitchen Sink in Flash Gordon: Volume 6 1943-1945 - Triumph in Tropica, copies of which can be obtained relatively cheaply from online sellers. You can read William Patrick Raymond's review and summary here and the strip itself here (courtesy of Art Lortie).

- Flash Gordon: "Triumph in Tropica", by Don Moore & Alex Raymond (King Features Syndicate). This also appears in Flash Gordon: Volume 6 1943-1945 - Triumph in Tropica and William Patrick Raymond's write-up is here. Art Lortie has again made the comic available here.

- The Spirit: "For the Love of Clara Defoe", by Manly Wade Wellman, Lou Fine and Don Komisarow (Register and Tribune Syndicate). This story was reprinted in Volume 9 of Will Eisner's The Spirit Archives, which is available from online booksellers. Art Lortie has made it available here.

- Superman: "The Mysterious Mr. Mxyztplk", by Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster (Detective Comics, Inc.). Originally appearing in Superman #30, this story has often been reprinted (see the DC Comics Database), most recently in The Superman Archives Vol. 8 (which appears to be in print in expensive hardback). It also appears in Superman: The Greatest Stories Ever Told, Vol. 2, second hand copies of which can more cheaply be obtained. The amazing Art Lortie has posted it here.

Best Dramatic Presentation, Short Form

- The Canterville Ghost, screenplay by Edwin Harvey Blum from a story by Oscar Wilde, directed by Jules Dassin (Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM)). This is available in two parts on Dailymotion, with the image inexplicably inverted from left to right. Part 1 and Part 2. It can also be watched uninverted on ok.ru or as uploaded by Art Lortie.

- The Curse of the Cat People, written by DeWitt Bodeen, directed by Gunther V. Fritsch and Robert Wise (RKO Radio Pictures). This film can also be seen on ok.ru. Art Lortie has made it available here.

- Donovan's Brain, adapted by Robert L. Richards from a story by Curt Siodmak, producer, director and editor William Spier (CBS Radio Network). This radio drama can be downloaded or streamed from the Internet Archive. Art Lortie has uploaded it in two parts, here and here.

- House of Frankenstein, screenplay by Edward T. Lowe, Jr. from a story by Curt Siodmak, directed by Erle C. Kenton (Universal Pictures). This can be viewed on ok.ru or, courtesy of Art Lortie, here.

- The Invisible Man's Revenge, written by Bertram Millhauser, directed by Ford Beebe (Universal Pictures). The Internet Archive has this available to stream or download. Art Lortie has posted it here.

- It Happened Tomorrow, screenplay and adaptation by Dudley Nichols and René Clair, directed by René Clair (Arnold Pressburger Films). This can be viewed on YouTube.

Best Editor, Short Form

- John W. Campbell, Jr. was the editor of Astounding Science Fiction, of which in 1944 12 issues appeared, which can be seen here: January, February, March, April, May, June, July, August, September, October, November, and December.

- Oscar J. Friend edited Captain Future, Startling Stories, and Thrilling Wonder Stories. The Spring issue of Captain Future is available on the Internet Archive. The Spring, Summer, and Fall issues of Startling Stories can also be seen there, as can the Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter issues of Thrilling Wonder Stories.

- Mary Gnaedinger edited Famous Fantastic Mysteries, whose March, June, September, and December 1944 issues can be read on the Internet Archive.

- Dorothy McIlwraith was in 1944 the editor of Weird Tales, whose January, March, May, July, September, and November 1944 issues can be seen on the Internet Archive.

- Raymond A. Palmer edited Amazing Stories and Fantastic Adventures in 1944. On the Internet Archive one can see the January, March, May, September, and December issues of Amazing Stories and the February, April, June, and October issues of Fantastic Adventures.

- W. Scott Peacock edited Jungle Stories and Planet Stories in 1944. No issues of Jungle Stories are available on the Internet Archive, which may be just as well, but the site does have the Spring, Summer, Fall, and Winter issues of Planet Stories.

Best Professional Artist

- Earle K. Bergey in 1944 provided cover art for Captain Future, Startling Stories, and Thrilling Wonder Stories. His ISFDB has links to the entries for the issues he provided covers for, where his art can be seen.

- Margaret Brundage provided the cover art for the May 1944 issue of Weird Tales and to the story "Iron Mask" within that issue. If her ISFDB entry is to be believed then that is all she did in 1944.

- Boris Dolgov did the cover for the March 1944 of Weird Tales. He also provided interior art for every 1944 issue of the magazine, so if you browse through the links given with Dorothy McIlwraith above you will see more examples of his work.

- Matt Fox did the cover for the November 1944 issue of Weird Tales. He also provided interior art for the poem "The Path Through the Marsh" and story "The Weirds of the Woodcarver" in the September issue of the magazine.

- Paul Orban appears not to have done any cover art in 1944, but he did interior art in every issue of Astounding Science Fiction that year, so check out the links given with John W. Campbell above for examples of his work, which are typically credited simply to "Orban".

- William Timmins did all the 1944 covers for Astounding Science Fiction, apart from the July issue, so follow the links given above in Best Editor for John W. Campbell to see examples of his work.

Best Fanzine

Joe Siclari and Edie Stern of the Fanac Fan History Project have put together a Retro Hugo Awards page for

Fan Hugo Materials for Work Published in 1944, with links to scanned copies of the finalist fanzines from 1944:

The Acolyte (edited by Francis T. Laney and Samuel D. Russell),

Diablerie (edited by Bill Watson),

Futurian War Digest (edited by J. Michael Rosenblum),

Shangri L’Affaires (edited by Charles Burbee),

Voice of the Imagi-Nation (edited by Forrest J. Ackerman and Myrtle R. Douglas), and

Le Zombie (edited by Bob Tucker and E.E. Evans).

Best Fan Writer

The FANAC Retro Hugo Awards page for

Fan Hugo Materials for Work Published in 1944 also links to examples of writing in 1944 by the fan writer finalists, who are Fritz Leiber, Morojo (Myrtle R. Douglas), J. Michael Rosenblum, Jack Speer, Bob Tucker, and Harry Warner, Jr.

And that's it. I hope readers find this useful. Have fun reading and voting in the Hugo Awards.

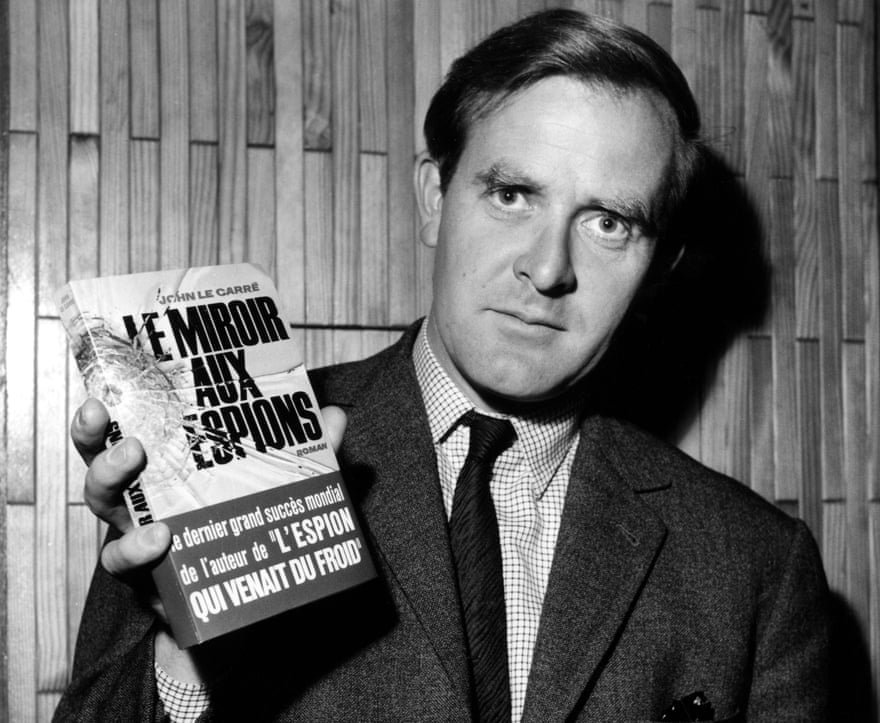

The passing of popular novelist John le Carré has led many people to write things about him and his works, which mostly dealt with spies working for the British intelligence services. If you've never read his work, then I say dive in as his books are very impressive, somehow turning his stories about people perusing files and going to meetings (plus occasionally flying off to do mysterious things in strange places) into dramas of high import that seemed to say something about the world we live in. A good starting point is The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, the book that made his name. From there I recommend progressing to the Karla trilogy (Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, The Honourable Schoolboy, and Smiley’s People) and then reading whatever ones of his books you come across.

The passing of popular novelist John le Carré has led many people to write things about him and his works, which mostly dealt with spies working for the British intelligence services. If you've never read his work, then I say dive in as his books are very impressive, somehow turning his stories about people perusing files and going to meetings (plus occasionally flying off to do mysterious things in strange places) into dramas of high import that seemed to say something about the world we live in. A good starting point is The Spy Who Came In From The Cold, the book that made his name. From there I recommend progressing to the Karla trilogy (Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy, The Honourable Schoolboy, and Smiley’s People) and then reading whatever ones of his books you come across.

In the first of the Karla trilogy le Carré presents us with a Smiley who has been forced into early retirement, but who starts to suspect that Karla, the Soviet spymaster, is running an agent at the heart of the British intelligence service. The book follows his investigations, which range backwards over past intelligence operations and include a fateful but enigmatic meeting between Smiley and Karla himself, when the latter was a field agent. The book gains much of its power from parallels with the real-life penetration of the British intelligence services by Soviet spies, with Smiley investigating analogues of actual Soviet moles. It is very evocative of a country struggling to find its way after losing its empire, its elite gripped by malaise as they face the fact that their country is now just a camp follower of the United States.

In the first of the Karla trilogy le Carré presents us with a Smiley who has been forced into early retirement, but who starts to suspect that Karla, the Soviet spymaster, is running an agent at the heart of the British intelligence service. The book follows his investigations, which range backwards over past intelligence operations and include a fateful but enigmatic meeting between Smiley and Karla himself, when the latter was a field agent. The book gains much of its power from parallels with the real-life penetration of the British intelligence services by Soviet spies, with Smiley investigating analogues of actual Soviet moles. It is very evocative of a country struggling to find its way after losing its empire, its elite gripped by malaise as they face the fact that their country is now just a camp follower of the United States.