I somehow never got round to properly writing about 2024's Le Guess Who festival, which left many people disappointed [CITATION NEEDED]. I won't make that mistake this year. But before talking about the festival itself, I need to describe how we got there. The first time my beloved and I went to Le Guess Who, we flew. Then we switched to travelling overland to Utrecht (boat and train to London, Eurostar to Rotterdam, then local train to Utrecht) with a stopover in London. But this year we decided to try making the journey overland to Utrecht in one day, skipping the London stopover. This was partly for financial reasons (a night in London costs money) but also for cat reasons, as cat name of Billy Edwards is getting on a bit and we like to leave her on her own as little as possible. So it was we booked a sail-rail ticket from Dublin that would get us into Euston station in London about 20 minutes before the recommended arrival time in nearby St. Pancras for the day's last Eurostar to Rotterdam. Our time window was very tight, with a delay on our train to London of 30 to 40 minutes meaning that we would definitely miss the Eurostar. But live lives of gay abandon and so we were willing to take the risk.

And in truth, everything worked. We reached St. Pancras in good time and then had the usual uncomfortable wait in the overcrowded holding area on the other side of the security gates before we were allowed board our train. We did have some vague contingency plans for if we missed the Eurostar, of which the night bus to Rotterdam was the cheapest but most terrifying. The more expensive (but not crazily so) alternative would be the night boat from Harwich to Hoek, for which the connecting train leaves Liverpool Street at a time making it easy to catch.

But as I said, it all worked and we arrived at our hotel at around midnight and once they let us in (which took worryingly long) we hit the sack. And then our Thursday began with the first mimosa breakfast of the weekend. We were now ready for whatever Utrecht had to offer.

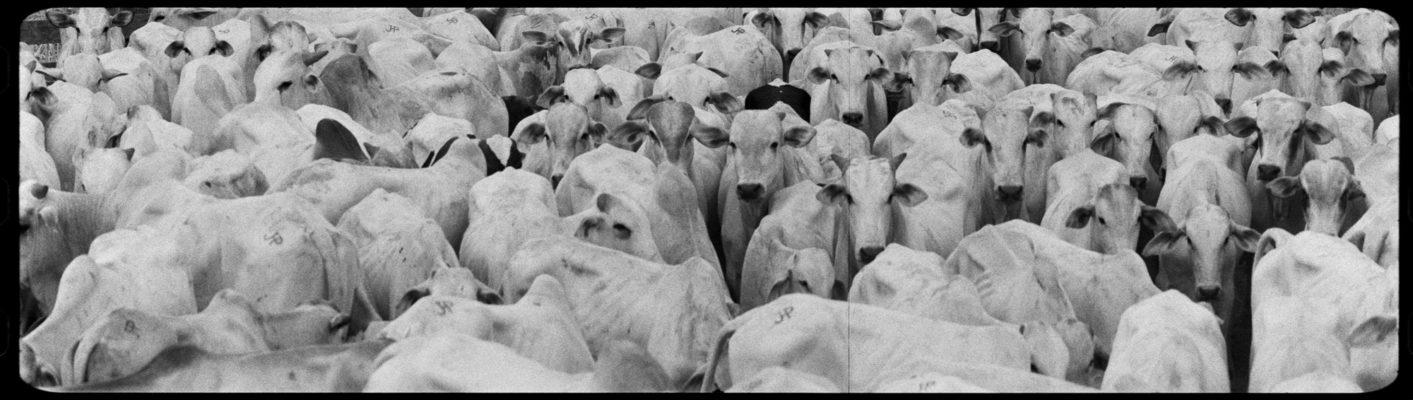

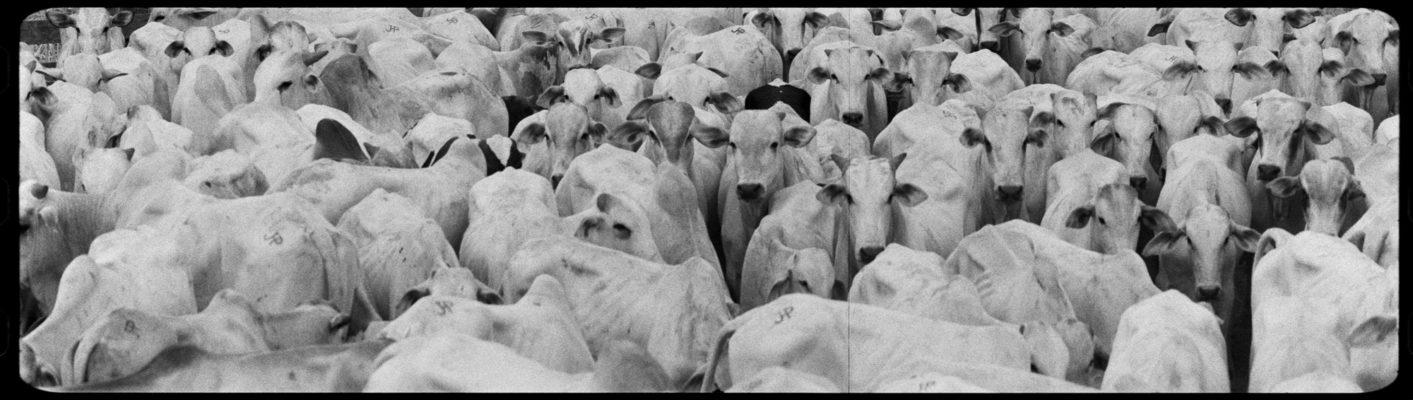

Our first stop was the Centraal Museum, where two Le Guess Who related exhibitions were taking place. The first of these was Broken Spectre by Richard Mosse. He is an Irish artist whose The Enclave was one of the highlights of the 2022 LGW. That work saw footage projected onto multiples screens of material shot in the Democratic Republic of Congo in a rebel-controlled enclave, with an infra-red colour filter making everything look purple. Broken Spectre was in some ways a more conventional film work, in that it was projected onto a single screen (or maybe several screens that were all in the same place), which meant that you weren't having to keep looking around behind you to see what was happening on other screens. The subject matter of this one was environmental devastation in the Amazon as the forest is destroyed to make way for cattle farming, with an invasion of gold miners polluting everything else being the icing on the habitat destroying cake. It's a pretty grim watch, from the scenes in a vast industrial abattoir as cows are butchered, to the scenes of forest burning and on to indigenous people being driven off their land. It is such a downer that it didn't make for a great start to the festival; in retrospect this would have been better watched as a palate cleanser on the second day.

Our first stop was the Centraal Museum, where two Le Guess Who related exhibitions were taking place. The first of these was Broken Spectre by Richard Mosse. He is an Irish artist whose The Enclave was one of the highlights of the 2022 LGW. That work saw footage projected onto multiples screens of material shot in the Democratic Republic of Congo in a rebel-controlled enclave, with an infra-red colour filter making everything look purple. Broken Spectre was in some ways a more conventional film work, in that it was projected onto a single screen (or maybe several screens that were all in the same place), which meant that you weren't having to keep looking around behind you to see what was happening on other screens. The subject matter of this one was environmental devastation in the Amazon as the forest is destroyed to make way for cattle farming, with an invasion of gold miners polluting everything else being the icing on the habitat destroying cake. It's a pretty grim watch, from the scenes in a vast industrial abattoir as cows are butchered, to the scenes of forest burning and on to indigenous people being driven off their land. It is such a downer that it didn't make for a great start to the festival; in retrospect this would have been better watched as a palate cleanser on the second day.

We talked a bit about what made Broken Spectre so much grimmer than intense artworks included in previous years of Le Guess Who. The Enclave does include some dead bodies but overall it just feels weird rather than depressing as you never really get much sense of what is actually going on. There was a Forensic Architecture exhibition at our first Le Guess Who that examined a number of horrendous events. That was pretty grim too, but my beloved reckoned that it was less upsetting than Broken Spectre was that it felt like Forensic Architecture were gathering evidence that might conceivably be used one day to hold the perpetrators to account (most likely an illusory hope, particularly for the Israeli killers of schoolchildren). But with Broken Spectre it's just a shit show and I'm not even sure there is anyone to hold to account, as it felt like we are dealing here with vast socio-economic forces.

There is a bit in the film where this Yanomami woman is complaining to camera about how her people are being driven off their land, and then she starts giving out about the film itself, basically saying "What good is your stupid film going to be for us?" And it's a fair point, if all that happens is people watch the film and feel sad about a situation they see as intractable. I also found myself wondering whether the film might land differently with meaters, who I could imagine thinking "It's sad the forest is being destroyed, but I've got to get my burger!".

The film did provide a link to where you can donate money to the Hutukara Yanomami Association.

The film did provide a link to where you can donate money to the Hutukara Yanomami Association.

The other LGW-related piece in the Centraal Museum was called Drama 1882 and was a film by Wael Shawky of a stage play (or opera) about the ultimately unsuccessful revolt by Egyptian army officers led by Ahmed 'Urabi against the country's ruler, the Khedive, seen as in thrall to foreign powers. The film shows the progress and ultimate defeat of 'Urabi by a British expeditionary force through song and stylised movement that hovers this side of counting as dance, and manages to be a fun watch despite being about the irresistible power of imperialism.

The other LGW-related piece in the Centraal Museum was called Drama 1882 and was a film by Wael Shawky of a stage play (or opera) about the ultimately unsuccessful revolt by Egyptian army officers led by Ahmed 'Urabi against the country's ruler, the Khedive, seen as in thrall to foreign powers. The film shows the progress and ultimate defeat of 'Urabi by a British expeditionary force through song and stylised movement that hovers this side of counting as dance, and manages to be a fun watch despite being about the irresistible power of imperialism.

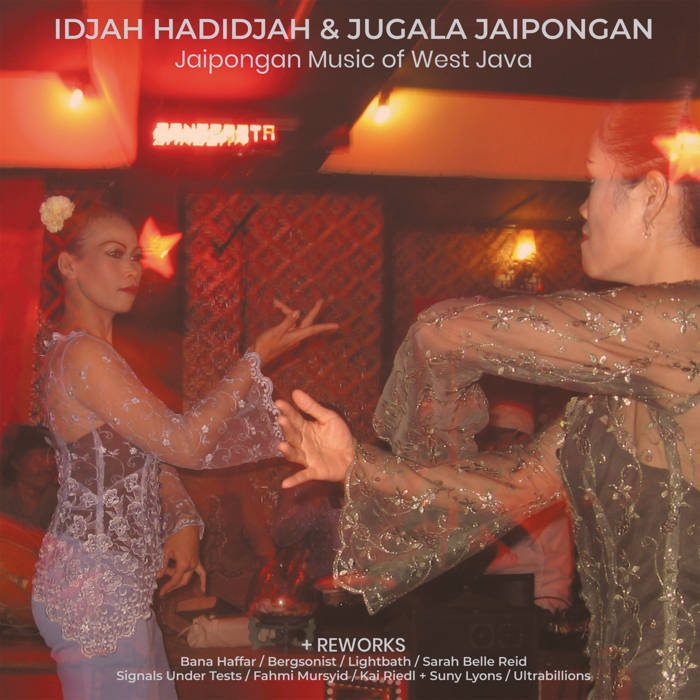

You may at this point be wondering if this festival featured any actual musical performances. Fear not. The first actual act of this kind we saw was Omar Hayat, a Gnawa musician from Essaouira in Morocco (where I went on holidays some years back; I don't remember meeting him). Gnawa is I think linked to an ecstatic version of Sufi Islam popular in those parts. Omar is an old-ish guy playing some kind of stringed instrument while some younger guys played percussion stuff. But also the younger fellows did some acrobatic dancing, making this Sufi Islam religion a bit different from the kind of staid Christianity I grew up. It was generally felt that Mr Hayat won the milking-the-audience award for Le Guess Who 2025.

Valentina Magaletti was one of the curators of this year's festival, playing several times over the weekend. We did catch a bit of her playing with Upsammy in the Ronda (the largest Tivoli Vredenburg venue that isn't the Grote Zaal) but they had already started when we came in and it was hard to connect with from the back, so we made our excuses and left. But we did come down good and early to see SUNN-O))) and in fact I was able to get right to the front of the stage, to the extent that I could hold my phone up past the onstage monitors to photograph the band. If you've ever seen SUNN-O))) you'll get the basic idea: they wear capes, they play guitars very loud, they have loads of speakers onstage, they fill the stage with dry ice, their music consists of very slow guitar chords, and so on.

On this occasion it was just the core members of SUNN-O))), Stephen O'Malley and Greg Anderson, so they didn't have the weird Hungarian guy dressed as either a tree or one of the Cylons from original Battlestar Galactica or any of the other musicians they sometimes play with. This brought me back to times when I saw them play first and I enjoyed their ritualistic set a lot, although I can see why someone might feel that it gets a bit repetitive.

Did I then see a bit of forward thinking jazzers [Ahmed] playing up in Cloud Nine (at the summit of the Tivoli Vredenburg, although there are rumours of a secret other venue even higher in the building)? It is possible but as no documentary evidence of this having occurred exists I am not disposed to discuss such an incident at this present time.

And so to bed.

images:

Broken Spectre cows (Photo Elysée: "Richard Mosse: Broken Spectre")

Broken Spectre Yanamami (Atmos: "Richard Mosse: Depicting Ecological Collapse in the Amazon")

Drama 1882 (Le Guess Who: "Centraal Museum presents Wael Shawky and Richard Mosse at LGW25")

My Le Guess Who pictures