I went to London for a celebration of the centenary of the birth of screenwriter Nigel Kneale. Organised by Jon Dear, with the glamorous assistance of Toby Hadoke, Howard David Ingham, and Andy Murray, this was a day of screenings and panel discussions in the Crouch End Picturehouse.

The first panel looked at Kneale's early work with the BBC, which started with literary adaptations and then moved on to The Quatermass Experiment in 1953 and its follow-up serials in 1955 and 1958, as well as his adaptation of Nineteen Eighty-Four in 1954. These were the event television of their time, with questions being asked in parliament about Nineteen Eighty-Four and the streets reportedly emptying when Quatermass was on, though of course this was also a time when there was only one British TV channel. The details of television's early years brought up the panelists were fascinating. At that point television, even drama, was still mostly broadcast live; pre-recording was only used for material shot outside, which was still a bit of a novelty. Drama was also conceived in very theatrical terms, with Reginald Tate, the actor playing Quatermass in the first series, taking a bow at the end of the last episode.

One of the panelists had looked up what was actually shown on the BBC on the day the first episode of The Quatermass Experiment was shown. Initially there was alternating coverage of Royal Ascot and Formula One motor racing, then a short piece of children's programming, more Ascot and motor racing, and a news reel, all interspersed with interludes when nothing was being shown. And then a warning from the announcer that the following programme might not be suitable for children or those of a nervous disposition, before the ominous tones of Holst's "Mars" brought us into the world of Professor Quatermass and his experiment.

Another point made by the panelists (and one repeated through the day) was that for all Nigel Kneale's best remembered work dealt with science fiction and horror themes, he never thought of himself as a genre writer and was indeed very dismissive of science fiction. Partly that derived from his having a somewhat limited sense of what constituted science fiction, seeing it as something characterised by the US pulp tradition and screen material inspired by it. Science fiction fans will rightly grumble that the genre has so much more to offer. And yet if you look at what passes for screen science fiction now you see that it is dominated by films in which people in stupid costumes punch each other or by formulaic Trek Wars crap that is cosily familiar rather than in any way challenging. It's like the pulp tradition has taken over science fiction, so maybe Kneale was right to dismiss the genre entirely.

This discussion preceded a screening of "Contact has been established", the first episode of The Quatermass Experiment. Professor Quatermass is the director of a British space programme that has sent a manned rocket into orbit, but something has gone wrong. Eventually the rocket crash lands in south London, but inexplicably there is only one of the three astronauts left inside the capsule.

One thing that struck me with this episode was how the shadow of the Second World War hangs over Kneale's early work. After the rocket lands on a residential street displaced locals reference the Blitz, with one confused woman seeming to think that the V2 rockets are back. The later Quatermass and the Pit sees people finding something during tunnelling that they initially think is an unexploded German bomb (that drama's nightmarish climax sees people consumed by an urge to exterminate the different, which also evokes the horrors of the Third Reich). And Kneale's Nineteen Eighty-Four feels very much like it is set in a world where the Second World War never stopped (which I think was Orwell's intention but it is maybe less obvious to us when reading his book). I suppose in the 1950s the war was still very recent, with some food rationing still in place when the first Quatermass episode was broadcast. That the war, or something like it, could start up again must have been a fear forever lurking below the surface. The depiction of a street destroyed by a rocket must have triggered uneasy memories on the part of many viewers (and for all the studio bound nature of the first Quatermass episode, the ruined house set is surprisingly effective).

"Contact has been established" was followed by Tom Baker reading Kneale's short story "The Photograph"; the story is from much further back but this was broadcast in 1978, when Baker had only recently departed from Doctor Who (ironic in that Kneale thought Doctor Who was rubbish but also resented how its producers lifted his plots and themes). After a short break Jon Dear talked to Douglas Weir of the BFI about the restoration of Kneale's Nineteen Eighty-Four (out now (finally) on DVD and Blu-Ray); having seen that some years ago at Loncon I am looking forward to catching it again in all its restored glory.

Then we had a panel on Nigel Kneale in the 1970s. This was Kneale's folk horror period, with ancient evils supplanting the dangers of science gone wrong in his work (though arguably the danger of chthonic terrors from the past was also a theme appearing in some of his earlier work, notably Quatermass and the Pit, while the 1970s still saw Kneale engaging with science fiction themes in the likes of The Stone Tape and the final 1979 Quatermass series). By now of course television was a much more mature medium, broadcast in colour with drama no longer going out live. And there were more channels in Britain (three, to be precise). TV was also edgier: for all that Mary Whitehouse was clipping its heels, much more could be shown now than in the 1950s. There was an interesting point made by Una McCormack about how not all of this lack of inhibition in the 1970s was necessarily great, with the television and cinema of the era sometimes seeing sexism slide into outright misogyny (think about how common sexual assault of women is in notable works of the decade); she talked of Kneale acknowledging this and reacting against it in the likes of Murrain or the Beasts episode "Special Offer". You could see something similar in The Stone Tape, where Jane Asher plays almost the only woman in a drama otherwise featuring a lot of often boorish men.

That was followed by a screening of Murrain, originally broadcast by ITV as part of the Against the Crowd anthology series. The film is based on two conflicts: the young vet representing science and modernity versus the superstition of the country folk, and then same superstitious country folk versus the eccentric old woman they believe to have cursed them. It makes for disconcerting viewing as it is never quite clear where your sympathies are meant to lie. Well, the vet is always operating with the most noble of motives, but beyond that it gets more complicated. Are the countryfolk bad because they are persecuting an old woman for no crime other than being a bit odd? Or is the old woman actually an evil witch who has brought a curse down on her neighbours? Or is she a woman of power who is merely striking back against her neighbours' persecution? The drama also retains an ambiguity as to whether the old woman is actually possessed of sinister powers, or whether the various ailments afflicting those who have slighted her are psychosomatic (which could be the case even if the old woman thinks she has cursed them). On the other hand, the farmer's pigs are actually suffering from a mysterious sickness (the murrain of the title), something that for them is unlikely to result from a belief in witchcraft.

Murrain is also surprisingly funny. Not funny all the time, but it has its moments. Like when the vet is in the village shop trying to buy stuff for the old lady. He asks the shopkeeper if she has any olives or chorizo; she gives him a look suggesting there is not much demand for such fripperies in these parts.

Murrain also gives us the great phrase from the vet, "We don't go back", with which he asserts his confidence that science will always provide the answers and that the old ways of superstition have nothing to offer us. The phrase gave Howard David Ingham the title for their book on folk horror, because the whole genre is largely based on the idea that maybe we will go back actually. By the end of Murrain even the vet's confidence in science seems to be shaken, for all that the drama's climax remains ambiguous.

That was followed by a panel on Kneale on film. For all that he wrote primarily for television, there are a good number of films based on his work or else scripted by him. Hammer made films of the three 1950s Quatermass series, the first two in the 1950s while Quatermass and the Pit (the best by a considerable margin) did not appear until 1967. He wrote some other films for Hammer (Abominable Snowman and The Witches) as well as an adaptation of H. G. Wells' The First Men in the Moon (which seemed to be always on television when I was a child). And he did some non-genre work (including, surprisingly to me, adaptations of John Osborne plays). But it was hard to escape the feeling that film was not really his medium, with his writing for the big screen being littered with projects that were stillborn or ended up as compromised failures (e.g. Halloween 3). Cinema is a more difficult medium for writers, with the amount of money riding on a picture meaning that someone like Kneale was never going to be given the kind of free rein he had on television.

And then we had a short clip from The Quatermass Xperiment [sic], the 1955 Hammer film adaptation of the first Quatermass series. A little girl playing on her own meets what we know to be a man transforming into something else, in a scene that cannot but evoke a disturbing counterpart in the 1931 film of Frankenstein. The girl was played by Jane Asher, who started out as a child actor. We then had the excitement of Jon Dear interviewing Jane Asher (Jane Fucking Asher!) as an introduction to a screening of The Stone Tape, in which she played the leading role.

Asher lent the day an air of star quality and was an engaging and entertaining interviewee. I was particularly amused by how one of her anecdotes pivoted to "He was a lovely man" when she discovered that its subject (a Stone Tape collaborator) was still alive. I had to admire her making a long round trip to attend the event, particularly given that she did not stay for the screening (she mentioned hating seeing herself on screen, something which I understand is not uncommon among actors). I was also struck by how there was an accidental echo of The Stone Tape in her appearance in the Picturehouse. In the TV drama she plays almost the only female character, isolated in a world of blokey blokes, while the Nigel Kneale Centenary event was also a pretty male-dominated affair, both in terms of the audience and the programme participants (there were several manels and no panel with more than one female participant); hopefully this event went better for her than The Stone Tape did for the character she played.

And so to The Stone Tape itself. As with almost all the screenings, this was my first time seeing this, though it is something I have heard discussed at folk horror online events. It is a feature length TV play first broadcast on BBC 2 in 1972. It mixes science fiction and horror, being in part a ghost story but also attempting to offer a scientific explanation for hauntings (the idea that places can somehow record events that have taken place in them, now often referred to as the Stone Tape theory, for all that the idea preceded the drama). And the play itself is about recording, as its premise is that a team of recording engineers are setting up in a country house to research new audio technologies. The house being haunted presents some challenges, but when they hit on the Stone Tape theory they start thinking that this could maybe be harnessed into a revolutionary new audiovisual recording medium. But this is horror so things do not entirely work out.

I mentioned that Jane Asher plays (almost) the only female character in The Stone Tape, a computer programmer. The sexism of the era is a bit of a theme to this one, with the married head of the project in a problematic relationship with her, while she often finds herself patronised by her colleagues. But what is really striking about the drama is the racism. The researchers are in competition with Japanese rivals, and every time they are mentioned (usually as "The Japs") the characters switch into the kind of parody Asian accent and facial contortions that would disbar you from public office if a recording of you doing it were to surface. And also the company they work for, Ryan Electrics, is owned by an Irishman; he never appears but whenever he is invoked the characters switch into stage Irish accents. Yet it is hard not to see all this as signs of weakness rather than confidence. It must gall these arrogant Englishmen to be taking orders from the scion of one of their former colonies. And for all their mocking of the Japanese, it is stated fairly explicitly that unless the team achieve their sonic breakthrough the British audio industry will be soon wiped out by its East Asian competitors. The sexism might also mask a blokey unease that women are now moving into the workforce and occupying roles that would previously have been the preserve of men.

I should also mention that The Stone Tape features an amazing BBC Radiophonic Workshop soundtrack.

I was talking after the screening to one of my neighbours about how Ireland and the Irish people are a bit of recurring theme for Kneale. As well as Ryan, he mentioned how in Quatermass II the revolt against the alien invaders begins on St. Patrick's Day and is spearheaded by Irish labourers. And there is an Irish drunk in The Quatermass Experiment. Irish names show up throughout Kneale's work. I'm not sure what the significance of this might be. Kneale was not from Ireland and as far as I know he did not have ancestors from here; he may never have visited the island. But maybe this is not so remarkable: there are lots of Irish people in Britain after all, and they are an easy kind of slight other to represent.

And then we had an odd thing, a live performance of You Must Listen a lost Nigel Kneale radio play broadcast in 1952. Again it combined technology and hauntings, with an initially comical tale of crossed telephone lines becoming more macabre as the intruding voice is revealed to be that of a dead person. It had a lot of characters, who were performed by programme participants and a few professional actors (these were not mutually exclusive categories). I was impressed by how Mark Gatiss, probably the most famous participant, took a relatively minor role.

You Must Listen reminded me somewhat of Robert Presslie's short story "Dial 'O' for Operator", in some respects a similar tale of crossed wires and temporal distortion, though in other ways rather different. Presslie's story did not appear until 1958, so it is possible Kneale's drama planted the seed in his brain.

The final panel looked at Kneale's legacy. Stephen Gallagher compared Kneale to Stephen King, in that both writers revolutionised horror by placing it in everyday contemporary settings (sadly no one noted that we were attending an event in Crouch End, setting and title of one of King's most effective short stories). There was also reference to the disturbing prescience of his late 1968 TV play The Year of the Sex Olympics, which prefigures much of the reality television that blights our age, with something like Naked Attraction almost looking like it took Kneale's play as a template. Mark Gatiss mentioned that at the peak of The League of Gentlemen's success, he tried to push the BBC's controller to commission a new series from Kneale, still living at the time. However, he was told that there was no place on the BBC for someone whose career started before the invention of the remote control.

And then the day closed with a screening of Quatermass and the Pit, the 1967 Hammer film version of the 1958-59 TV series. Directed by Roy Ward Baker and with a strong cast including Andrew Keir as Professor Quatermass, James Donald and Barbara Shelley as palaeontologists, and Julian Glover as an army officer. Like much of Kneale's work, this combines science fiction and horror, with Quatermass's space research interrupted by the discovery of strange hominid remains during construction work on an extension to the London Underground's Central Line; that initial find is followed by ever more disturbing revelations about the true history of humanity.

It is a stunning piece of work, with the tension building as the awful truth is gradually uncovered and the drama moves towards an apocalyptic climax. Maybe the closing section of the film is ever so slightly rushed, but Kneale nevertheless did an amazing job condensing a TV series of more than three hours into a film of 97 minutes, with the propulsive energy of the narrative carrying the viewer along without leaving them time to ponder possible logical gaps in what they are watching. Much of the horror comes from people realising things or just having an idea at the edge of their understanding: there is an astonishing scene early on where a tough policeman comes close to a breakdown merely be viewing odd graffiti marks in an abandoned house. As one of the panellists earlier remarked, The Quatermass Experiment is about an alien incursion happening now while Quatermass II has an invasion that began a couple of years ago, but in Quatermass and the Pit the alien invasion took place five million years ago and basically succeeded, profoundly altering the course of human development but not in a good way (this a year before the publication of Erich Van Daniken's Chariot of the Gods).

The film also looks amazing. It has the saturated colour of Hammer films of the era but somehow this all seems more impressive in what was then a contemporary context rather than being in some backward corner of Mitteleuropa. Like other Hammer films Quatermass and the Pit is also happy to focus much attention on the good looks of a female lead. Yet for all that Barbara Shelley appears in a succession of stunning outfits, she is never presented as the kind of sexy lady seen in other Hammer films (for comparison see her performance in the latter part of Dracula, Prince of Darkness); the film's poster is somewhat misleading in this regard.

And that I suppose was that. I enjoyed the event a lot, with the combination of programming and discussion working very well. The material shown to us was particularly well chosen, presenting a fascinating overview of Kneale's career, building like one of his works to a terrifying climax, in this case Quatermass and the Pit. The panels were full of interesting people whose insights greatly improved our enjoyment of the screenings and had me thinking of more things to watch. Overall the event had the feeling of a cosy SF con (there was even a slightly redux Lally Wall). Looking back though I found myself thinking about two things the panellists did not really touch on. The first was Kneale's non-genre work, only really mentioned in passing. There was a surprising amount of this, including an episode of Kavanagh QC (his last work according to IMDB), an adaptation of Sharpe's Gold, the previously mentioned John Osborne screenplays, and an adaptation of Wuthering Heights (which admittedly is semi-genre). What I was curious about here is whether in his work on these non-genre pieces he still somehow injected some Kneale magic into proceedings, or whether they are essentially pieces of generic hackwork that could have been written by anyone. The other thing I found myself wondering was whether Kneale ever considered moving into direction, thereby trying to become a proper auteur director rather than a writer who had to worry about how his work would be realised. Books like Into the Unknown by Andy Murray (on sale at the centenary event but sadly all copies were snapped up before I could buy one) or We Are The Martians (edited by Neil Snowdon) might provide further insights into these questions.

images:

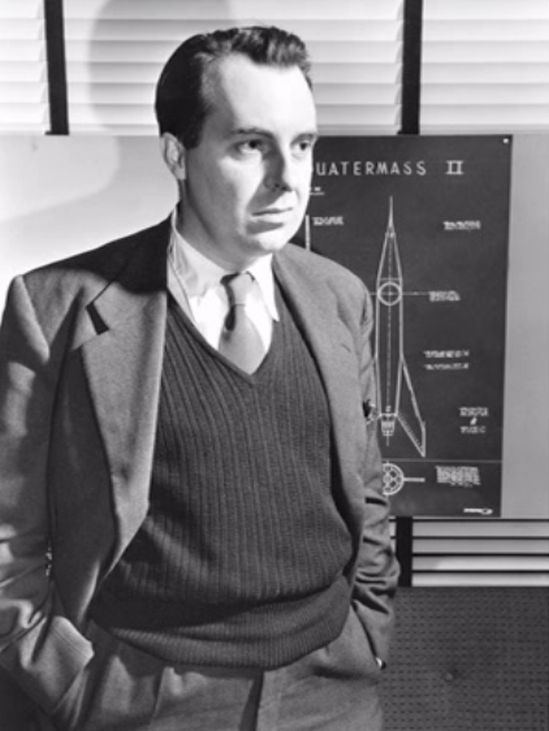

Nigel Kneale (Archivetvmusings, Twitter)

We Don't Go Back (Room 207 Press Shop)

Quatermass and the Pit poster (Wikipedia)

Barbara Shelley (Morbidly Beautiful: "Remembering an icon: Barbara Shelley")

More of my Nigel Kneale Centenary images here

More cat pictures here